Use these 6 philosophical razors to become a better thinker

What are philosophical razors and how they can make you a better thinker? In this post, we’ll look at six commonly used razors and how they can be applied.

What is a razor?

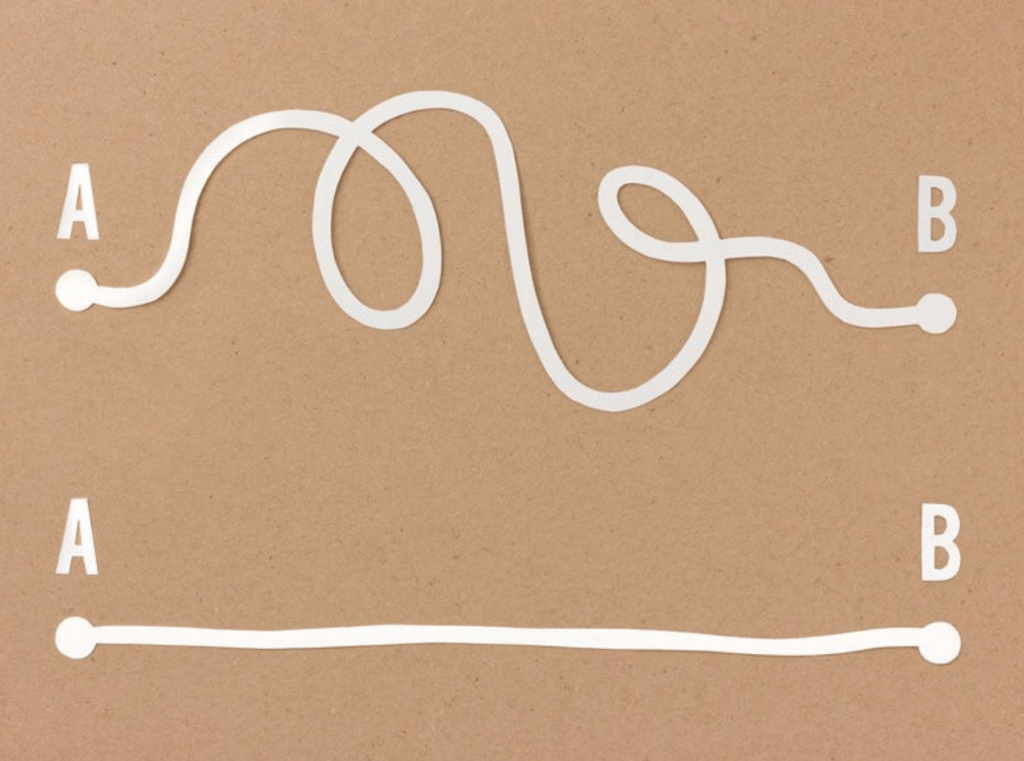

A razor is a rule of thumb that can be used to better explain, debate, or explore a topic. Just like an actual razor, a philosophical razor “shaves off” unlikely explanations or complexities. This, in turn, helps you think with more clarity and efficiency.

Razors originated in philosophy, but they’re useful whenever reason and logic are used to debate, discuss, or decide.

Don’t cut yourself

It’s important to emphasize that razors are rules of thumb and not universal laws. Think of them as short-hand logical tools. They can help you figure out what might be the explanation, but they aren’t clear-cut 100% things.

Occam’s razor, which I’ll talk about in more detail below, says that “simpler explanations are more likely to be correct” – and this is often the case. But sometimes, the more complex explanation is right. Sometimes calculus is the answer, and not arithmetic.

Be careful to avoid the trap of oversimplifying concepts or arguments that are more nuanced than you realize. It’s a healthy practice to get into the habit of questioning your assumptions and staying skeptical, especially about your most closely held positions.

Six philosophical razors and how to apply them

#1: Occam’s Razor

Meaning

Simpler explanations are more likely to be correct; avoid unnecessary or improbable assumptions. Entities should not be multiplied without necessity.

Example

Doctors are taught that “when you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.” This suggests that they should first think about what is a more common, and potentially more likely, diagnosis.

Clarifications & Common Misperceptions

Be careful not to misuse Occam’s Razor. Sometimes a phenomenon can only be explained thoroughly by assuming a great deal of complexity.

A lot of people misinterpret this razor as “the truth is more likely to be simple.” Rather, it’s saying that between competing explanations for the same phenomenon, answers with fewer assumptions are better.

The Bottomline

All things being equal, simpler answers are better because they have fewer assumptions. Or, as Einstein said, “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

#2: Grice’s Razor

Meaning

When in conversation with someone, respond to what the speaker meant instead of addressing the literal meaning of what they said.

Or, if you’re interested in an official, much more wordy definition from Paul Grice: “Conversational implications are to be preferred over semantic context for linguistic explanations.”

Example

If I miss my flight and say, “Oh, that’s perfect” – you should assume that contextual meaning of “perfect” (in this case, I’m being sarcastic), not that there is another definition of perfect.

Clarifications & Common Misperceptions

This razor assumes that you, the listener, understand what the other person is trying to say, even if they’re using the wrong language. However, if you don’t understand what someone is trying to say, you shouldn’t pretend that you do and carry on with the conversation. Stop and ask for clarification.

Another situation in which I think this razor’s use should be scrutinized is when someone says something problematic or offensive, but you infer that it was unintentional. You have to make a judgment call on whether to apply Grice’s razor. What is the context? If this is a one-off conversation, you might let it go. If, on the other hand, this is a colleague, there are implications of not addressing it. For example, the person could use this language in a setting that offends someone else and/or embarrasses them. How willing are you to accept those?

The Bottomline

Don’t take people literally and get into arguments over semantics. Usually, we know what others are trying to say, even if they’re not using precise language or the exact right words.

#3: Hanlon’s Razor

Meaning

Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by incompetence or stupidity.

Example

Imagine your father recently passed away and someone wishes you a Happy Father’s Day. Are they trying to upset you? Or did they honestly not know about your mother?

Mishaps are also common in our professional lives: wires get crossed, someone missed an email… someone gets snarky on a ping. It’s easy to slap labels on people (”they’re a jerk” or “they’re just difficult”). But more often, these behaviors are due to miscommunication, someone having a bad day, stress at work or home, or simply an accident. It’s unlikely that anyone woke up this morning determined to ruin your day.

Clarifications & Common Misperceptions

Just like Occam’s razor, be careful not to overapply this one. Sometimes people are being intentionally nasty.

However, I am in favor of applying Hanlon’s razor liberally. Misjudging the intent behind bad behavior often makes things worse and leaves us miserable. It narrows options and closes the mind.

If you see malice as the explanation for things that hurt you or make you mad, you’re less likely to try to improve the situation. Why would you? After all, they’re just a jerk, that’s who they are, and it can’t be helped.

In addition, believing that others are out to ruin your day requires the creation of a narrative to sustain this explanation. Usually, this narrative casts us as powerless victims, subject to the whims of external forces. This leaves us feeling discouraged and disheartened, and it makes it harder to remember that we always have agency and the potential to take action.

Lastly, I’ll note that it’s much harder to apply Hanlon’s razor to those closest to you: your friends, your family, and your close colleagues. These are more intimate, vulnerable relationships, and when someone messes up, it usually hurts more. Keep Hanlon’s razor in mind and try and work towards solutions.

The Bottomline

When people mess up, it’s often unintentional. Confucius summed all of this up nicely 2,500 years ago when he said, “He who takes offense when none is intended is a fool. He who takes offense when offense is intended is a bigger fool

#4: The Sagan Standard

Meaning

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

Example

If you claim that the earth is flat (cough famous NBA player cough), you better back it up.

Clarifications & Common Misperceptions

The Sagan Standard implies a proportional relationship between claims and evidence. Therefore, the bigger the claim, the greater the evidence needs to be.

There are some pitfalls with the Sagan Standard. What makes a claim “extraordinary”? And what exactly is “extraordinary” evidence? There are no firm definitions for these terms. What is extraordinary to you may be ordinary to me. And, what is extraordinary by today’s standards is likely to change.

A helpful definition comes from philosopher David Hume: “Hume precisely defined an extraordinary claim as one that is directly contradicted by a massive amount of existing evidence. For a claim to qualify as extraordinary there must exist overwhelming empirical data of the exact antithesis.”

To an extent, the Sagan Standard is fairly subjective. However, within groups, there does tend to be a generally accepted definition of what constitutes extraordinary, and Hume’s definition helps to add clarity. The lack of objectivity is less of an issue in the hard sciences, where claims and evidence can be more easily measured and quantified.

The Bottomline

Back up your arguments!

#5: Alder’s Razor, also known as Newton’s Flaming Laser Sword

Meaning

If something cannot be settled by experiment and reason, it is not worthy of debate.

The originator of this razor, Mike Alder, is also responsible for this alternate, more awesome name. Alder came up with it because this razor is inspired by Newton’s theories, and because a flaming laser sword is “much sharper and more dangerous than Occam’s razor.”

Example

You say blue, your favorite color, is better than red, my favorite color. Since this is an entirely subjective argument and there’s no way to prove which one of us is right, it’s not worth debating.

Clarifications & Common Misperceptions

Let’s get the obvious out of the way: it’s not practical to run experiments every time you disagree with someone, or there is a topic up for debate. And I don’t think that’s what Alder is suggesting. He’s not saying that if you and your partner disagree on whether you should take your toddler to the park or the pool, you should propose a hypothesis and devise an experiment to test it.

Alder’s razor makes the most sense in philosophical, scientific, and business contexts. Most software today is built using experiments that product teams fun to try out different features and designs.

The Bottomline

It’s gotta be able to be settled by experiment and logic, or it’s not worth debating.

#6: Popper’s Falsifiability Principle

Meaning

For something to be called a scientific theory, there has to be a way to prove it wrong.

Example

I took fish oil supplements to cure my flu, and after 5 days, I felt so much better! “Those supplements did it,” I say. But according to Popper, my theory about fish oil’s healing properties is not scientific, because there is no way to prove that they didn’t heal my flu.

Clarifications & Common Misperceptions

Though Popper’s principle refers specifically to scientific principles, I think it’s a good razor to keep in mind. Our brains are storytelling machines: they incessantly seek to create narratives that explain our experiences. But an explanation can be satisfactory without being true.

By applying Popper’s principle to our thinking and subjecting the narratives we tell ourselves to scrutiny, we can improve our thinking and get closer to the truth.

The Bottomline

It’s easy to verify any theory if we look for confirmation. However, truly testing a theory means attempting to falsify it. This idea is at the root of modern science.

Summary

- Occam’s Razor: All things being equal, simpler answers are better because they have fewer assumptions.

- Grice’s Razor: Don’t take people too literally.

- Hanlon’s Razor: When people mess up, it’s often unintentional.

- The Sagan Standard: Back up your arguments!

- Alder’s Razor: If it can’t be settled by experiment and logic, it’s not worth debating.

- Popper’s Falsifiability Principle: For something to be called a scientific theory, there has to be a way to prove it wrong.

Read More

- Interested in more ways to become a better thinker? Check out these 10 books to foster a growth mindset