Selective empathy: Why do we withhold empathy from one another?

Empathy is powerful. It can foster connection, strengthen relationships, and motivate us to help those in need. It can even make us more productive and has been found to drive innovation, engagement, and inclusion at work.

Given its potency and virtue, everyone deserves it.

Right?

In this post, we’ll take a closer look at the phenomenon of selective empathy: when we withhold empathy in some circumstances but not others. Who gets empathy and who doesn’t, and how might we be more thoughtful about empathy in our lives?

Selective Empathy: Refugees and Domestic Abuse Survivors

On February 24, 2022, Russian tanks swept into Ukraine. Overnight, millions were displaced from their homes. There was an outpouring of empathy for the people of Ukraine. Nations around the world, particularly in the west, opened their doors.

One month after the invasion, the US announced that it would welcome 100,000 Ukrainian refugees. Denmark, which is known for having some of Europe’s strictest anti-immigration laws, took in 36,000 Ukrainian refugees. The UK and France accepted over 140,000 and 118,000 refugees, respectively.

These are laudable decisions, and no doubt provided some measure of respite to hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians forced to flee their homes.

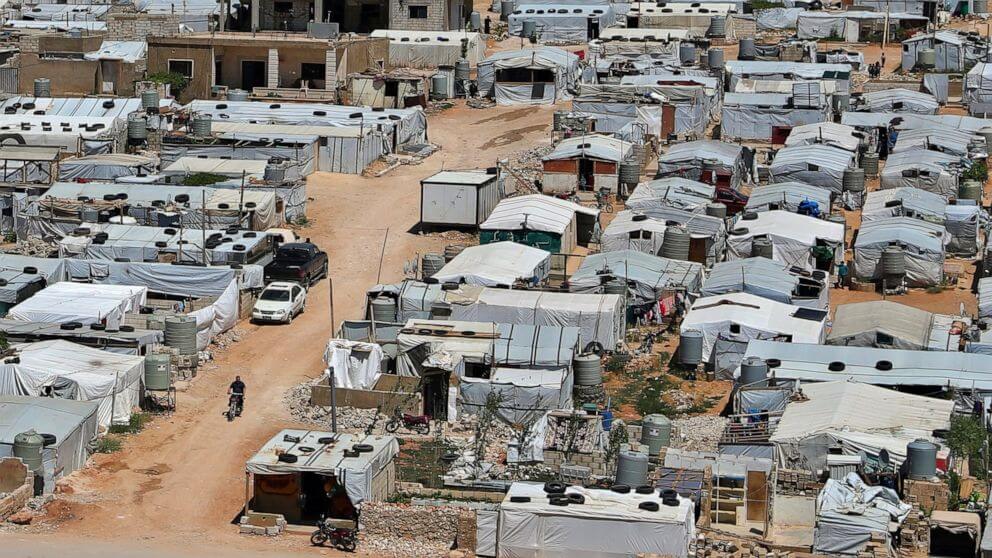

However, this spirit of magnanimity was nowhere to be found only a few years earlier when millions of Syrians were driven from their country during that nation’s civil war. Many western nations plainly refused to accept Syrian refugees.

According to a 2021 UN report – out of the nearly 7 million Syrians forced to leave Syria, only 1 million live in Europe, with 70% of them hosted by Sweden and Germany. To date, the US has accepted 8,500. The UK accepted 11,000, and France accepted 19,000.

The differing responses to the Ukrainian and Syrian refugee crises have prompted uncomfortable questions in the west, though some, like France’s far-right presidential contender Eric Zemmour, have been blunt and unabashed in their explanations:

“Everyone knows that Arab or Muslim immigration is too distant from us and it’s more difficult to acculturate and assimilate them. So effectively, we are closer to European Christians,” he said.

This is an example of what researchers call “selective empathy” which is when we empathize with one group but refuse the same empathy to others of a different group.

Another smaller-scale example involves the wife of white nationalist Richard Spencer, who in 2018 accused him of abuse, including an instance in which he attempted to punch her in the face while she was 9 months pregnant.

Commenters, many of whom were women, dismissed her, saying that she had gotten what she deserved, or that she should have thought twice before marrying such a horrible person.

It seems that despite lauding empathy as a good thing, in practice, we don’t believe that everyone deserves it.

Why is that?

A closer look at empathy: more complicated than you think

Empathy is the ability to share another’s emotions, thoughts, and feelings. Let’s take a closer look at where it comes from and how it works.

Empathy is an ancient human trait

It has obvious evolutionary utility, helping to foster social connection and cohesion that enables groups to work together and survive. Empathy is not limited to humans. Other animals, including many primates, exhibit empathy as well.

Empathy is genetic

Our levels of empathy are, in part, genetic. Empathy is distributed throughout the population like other traits, like height or hair color. This means that a significant portion of the population is born less empathetic. This doesn’t mean that people who are born less empathetic cannot learn to be more empathetic, or be impacted by cultural pressures. But these individuals may have to work harder at it than others who are genetically predisposed to be more empathetic.

Being less empathetic is advantageous in some contexts

This begs an interesting question: if empathy is so great, why aren’t we all born with high levels of it? Professor Peter Sterling writes,

“Apparently, because our species’ success gains from individuals on both sides of the bell curve. Obviously, we benefit from individuals with high empathy—sharers and carers. But we also benefit from high functioning individuals with low empathy. Three thousand years ago King David was an awesome leader even as he coldheartedly sent his lover’s husband to die in battle.”

Empathy is a “new” concept

While empathy has been around for a long time, it is a relatively new concept. The word empathy did not exist in English until 1908. It is a translation of the Einfühlung, which means “in feeling.” Over the last 100 years, social scientists and psychologists have debated the exact meaning and functioning of empathy. In the last 10-15 years, advances in neuroscience have enhanced our understanding.

Selective empathy: does empathy have a dark side?

Fritz Breithaupt, a professor at Indiana University, writes that empathy is a fundamental human trait. While it can strengthen relationships and motivate us to help one another, it is morally ambiguous. According to Breithaupt:

“People imagine that empathy can help resolve tensions in cases of conflict, but very often empathy is exactly that thing that leads to the extremes, that polarizes people even more… Humans are very quick to take sides. And when you take one side, you take the perspective of that side. You can see the painful parts of that perspective and empathize with them, and that empathy can fuel seeing the other side as darker and darker or more dubious.”

Observing conflict is one of the strongest triggers for empathy. It’s instinctual to pick a side. We empathize with the side we’ve chosen and lose the ability to empathize with the other side.

Psychologists and neurologists are finding that this process is subconscious: we don’t even realize what we’re doing. What’s more, it turns out it’s really difficult to empathize with people or a group that you don’t like.

Breithaupt cites an example from Northern Ireland, in which school administrators sought to improve relations between Catholic and Protestant youth in the early 2000s through an empathy-based curriculum. Students would learn about the motivations, perspectives, and atrocities committed by both sides.

It didn’t work. Studies found that this younger generation was more polarized than the one before it. Instead of developing more empathy for the other side, students “reorganized” the information to empathize more deeply with the people on their side.

This example illustrates an important truth: empathy is subject to in-group and out-group bias. Selective empathy is increasingly a product of the tribalism found in many societies around the world.

This is what happened in the case of the Syrian refugees attempting to enter Europe: Europeans were more inclined to empathize with the plight of the Ukrainians because they saw them as members of the same group.

British journalist Daniel Hannan wrote of the Ukrainians:

“They seem so like us. That is what makes it so shocking. Ukraine is a European country. Its people watch Netflix and have Instagram accounts, vote in free elections and read uncensored newspapers. War is no longer something visited upon impoverished and remote populations.”

Should a Netflix account and an Instagram handle be prerequisites for empathy? Is the suffering of a family in Ukraine qualitatively different than the suffering of a family in Syria?

A more nuanced approach to empathy

When we withhold empathy, we withhold understanding. We dehumanize instead of dignifying. This makes it easier to alienate, ignore, marginalize, or even harm those who we regard as unlike ourselves. In this scenario, empathy begins to look less like a virtue and more like a weapon.

With increasing levels of polarization and division in countries around the world, we should be on the lookout for selective empathy. We would also do well to be mindful of what researchers are learning about the way that empathy works, namely that our decisions about empathy are often subconscious.

Cultivate awareness of selective empathy

Remember that empathy is susceptible to in-group and out-group pressures. Think about places and times in which you might be triggered to selectively empathize in advance. But by practicing awareness of when you are responding to suffering with empathy and when you are not, we can catch ourselves when we are selectively empathizing.

Less empathy, more compassion?

In addition to cultivating more awareness of empathy and how it works, we should also practice compassion.

Compassion is defined as a feeling of deep sympathy for those stricken by misfortune, accompanied by a strong desire to alleviate the suffering.

While empathy refers to our ability to take the perspective and feel the emotions of another person, compassion includes the desire to help.

In practical terms, an empathetic response to your friend getting sick is to visualize what it feels like for them, whereas a compassionate response is asking your friend how they are feeling and how you can be of support.

Both are important, but amidst the focus on empathy, compassion can get lost in the shuffle.