4,000 Weeks: Why you’ll never get everything done and that’s okay. Part 2

[This is part 2 of a two-part post about Oliver Burkeman’s book: 4,000 Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. || Click here for part 1]

In this post, I am continuing my summary of Oliver Burkeman’s excellent book, 4,000 Weeks: Time Management for Mortals.

Burkeman’s thesis is that we should make better use of our precious and limited time (4,000 weeks is the length of an average lifespan) not by getting everything done, but by getting more of the right things done.

It’s an argument for focused ambition, for accepting the limitations that time imposes on all of us, and for fully inhabiting our reality.

In part 1 of this post, I covered four key ideas from the first half of Burkeman’s book.

- “More” is not the answer: why we can’t solve our problems by packing more in

- The perils of distraction: how distraction can prevent us from making meaningful choices about how to use our time

- Playing cat and mouse with the truth: ways that we hold ourselves back by avoiding the truth about our limited time

- The most important word in time management: one way that we can begin to reclaim our time

In part 2, I’ll cover four key ideas from the second half of the book.

- You’ll never be fully in control, and that’s okay

- “Now” is all we have

- Patience, the underrated virtue

- Our refreshing insignificance

You’ll never be fully in control, and that’s okay

The “human disease” refers to our quixotic quest for total control, certainty, and security in our lives. This condition is at the root of our obsession with time.

We are doomed to fail because, no matter how hard we may try, we will never:

Master time.

- Time is not something that can be possessed. It simply is. The only time available to us is the present.

Handle every demand made of us.

- Theoretically, there are an infinite number of demands that could be made of us. We don’t have time to handle them all. We will inevitably let others down, probably many times over the course of our lives.

Accomplish or pursue every ambition that feels important to us.

- There is simply not enough time.

Dictate or predict many of the things that will happen to us in our lives.

- People and events outside of our control will significantly impact us. We do not get to choose everything that happens to us.

Control outcomes.

- As Burkemen puts it: “the future just isn’t the sort of thing you get to order around like that.”

Be immune from suffering.

- Suffering is unavoidable. There will always be a risk of something bad happening, ranging from the mundane (embarrassment) to the catastrophic (the loss of a loved one).

Be ready for whatever happens to us.

- Inevitably, at some point in our lives, we will be ill-prepared for the situation that we find ourselves in.

This may be reading this and saying, “well, that was a downer,” but stay with me.

Limits are liberating

When we accept our limitations, Burkeman argues, we are liberated.

We no longer need to invest time and energy pursuing some future state that will never come to pass (the moment when we are certain we won’t fail, or the point at which we will finally feel totally confident and secure in who we are) and can use our time in ways that we find to be truly meaningful.

Another way to frame this is as surrender.

It’s about controlling the things that you can control (as far as time goes, the present moment is the only bit you are in control of), letting go of the things you can’t, and giving up the illusion that you’ll one day be the master of your time and fate.

It should be noted that this is not an argument against planning. Setting goals and making plans are essential tools in life.

But we would be wise to remember that a plan is merely a “statement of intent” about how you hope things will go and that the future is “under no obligation to comply.”

“Now” is all we have

We squander the present for the sake of the future.

Burkeman describes the “when I finally” mindset. This is a way of thinking that I am, I confess, prone to.

A person with a “when I finally” mindset is someone who makes their happiness, fulfillment, purpose, or worth conditional on some future achievement or state.

This sounds like:

- “When I get promoted to Vice President, I’ll be happy.”

- “Once I make my parents happy, I’ll feel fulfilled.”

- “When I get through this to-do list, I’ll feel in control of my time.”

- “If I lose 50 pounds, I’ll love and accept myself.”

This person imagines that when the glorious day arrives, they will, in a magical moment, finally feel whatever it is they have been withholding from themselves.

But instead, they are:

“treating the present solely as a path to some superior future state, and so the present moment won’t ever feel satisfying in itself. And even if this person does accomplish their goals, they will only find some other reason to postpone fulfillment until later on.“

This is a good way to waste a life. If we adopt this mindset, we are squandering the present for the sake of a future that doesn’t — cannot — exist. And if we imagine that fulfillment and purpose are in the future, we never have to confront the here and now. In this way, we can retain the illusion of control.

You are not an instrument

Capitalism encourages this kind of thinking. It is a system based on investing (or “instrumentalizing”) your available capital for the sake of future profits. Burkeman points out that you can apply this thinking to anything, including time, leisure, and child-rearing.

A former colleague told me about how, having taken a day off to recover following the completion of a particularly grueling project, found himself fretting about how to use his vacation time.

If he sat on the couch and watched Netflix all day (which is what he actually wanted to do), was he wasting his precious day? Should he instead invest it in something more productive, like working on the book he’s been talking about writing, or going on a hike?

When we see time as a commodity, we sap the present of any inherent value and instead ask about what it is earning us in the future. But, as Burkeman often writes, the present is all we ever have.

Patience, the underrated virtue

The tech-charged, ever-accelerating pace of modern life has made us impatient and anxious. But patience is essential for making the most of our time.

A good example of the connection between impatience and technology is internet speed. I am old enough to remember using dial-up internet. Downloading a song took hours. Downloading a movie took all day. It was fair game to wait up to five seconds for a webpage to load.

But now, only 15 years later, we feel an immediate tinge of impatience when an app takes longer than a second or two to load, or when our service is bad and Google Maps doesn’t update instantaneously.

Paradoxically, the faster things get, the more impatient we are. “With each invention,” Burkeman writes, “we are brought closer to the feeling of mastery over time.” The moment at which we will never have to wait for anything seems nearly at hand.

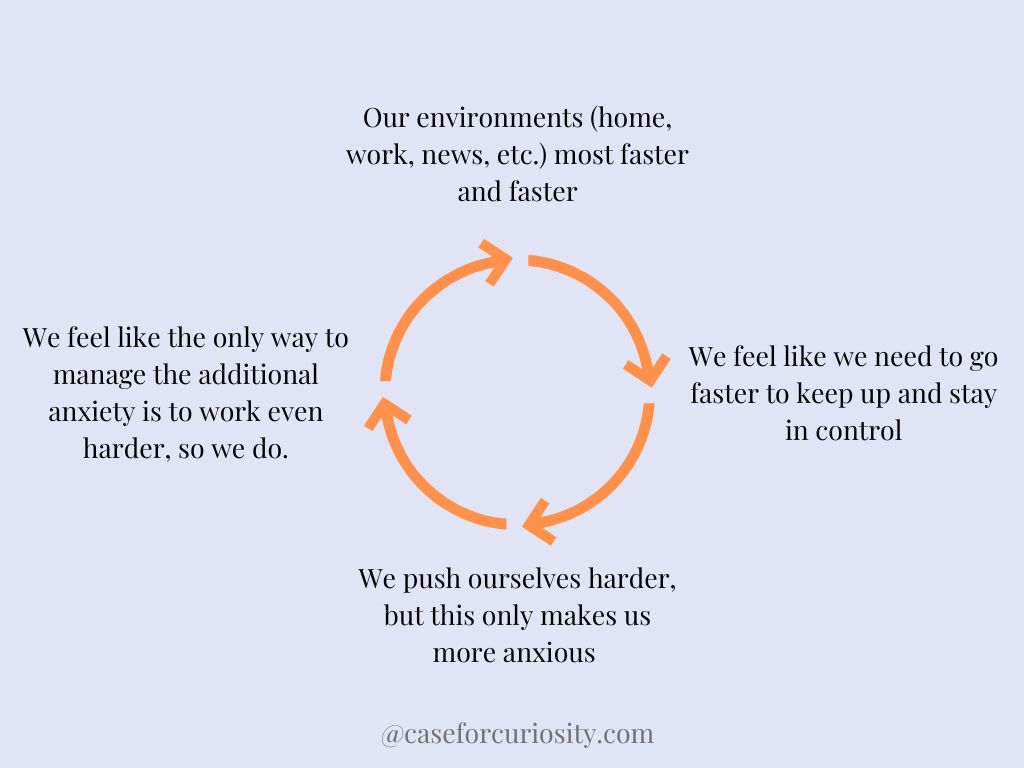

Speed has permeated many aspects of our lives to the extent that we have become addicted to hustle, activity, and busyness.

We are addicted to speed, to hustle, to activity, no hyperbole intended. Burkeman writes that, psychologically, our relationship to busyness is no different from any other addictive spiral.

Like any addiction, being busy feels good. There is a definite buzz to it. But as soon as we stop, withdrawal sets in, and you feel awful. It feels like the only thing that will make you feel better is more busyness.

Patience is the antidote to the sense of busyness that we find ourselves bombarded by

Practicing patience enables us to resist the constant urge to hurry. It allows things to take the time that they take. It is, against modern society’s standards, radical.

When we practice patience, we reclaim agency. We stop playing the dog that chases after every car that goes by. As a result, we are freer to do what counts and to derive satisfaction from doing it.

This isn’t easy. To be patient, we have to accept the discomfort of not knowing the answer right away, or letting things unfold without rushing them.

Our refreshing insignificance

“[There is a] gradiosity [that] takes the form of the belief that each of us has some cosmically significant Life Purpose, which the universe is longing for us to uncover and then to fulfill. But the truth is that the universe could care less.”

The truth, Burkeman writes, is what you decide to do with your life doesn’t matter all that much, at least on a cosmic scale (check out Tim Urban’s “Putting Time in Perspective” for an excellent and more comprehensive illustration of this idea).

The universe is 13.7 billion years old. Human civilization, encompassing everything from the time of Alexander the Great to the time of Abraham Lincoln to the present moment, is 6,000 years old. And as you know by now, the average human lifespan is just 4,000 weeks. When you zoom out, we are pretty small.

But we don’t feel this way. Thanks to egocentric bias, we all see ourselves as the main character in the story, at the center of the universe.

While the truth of our insignificance may feel like yet another downer (this stuff is actually uplifting, I promise!), it’s actually wonderful news.

When we embrace how small we are, we are released from the false notion that our actions matter on some cosmic scale. We no longer need to fret about achieving huge, big, magical things to feel like our lives are worthwhile.

Burkeman calls this “cosmic insignificance therapy.” We are free to consider how we might use our time in a way that is actually meaningful, even if that is, by history or society’s standards, relatively small.

It’s worth remembering that even for those of us who are uniquely remarkable — the Einsteins, the Turings, the Van Gohs — their achievements will someday be forgotten and/or destroyed.

Burkeman writes:

“Truly doing justice to the astonishing gift of a few thousand weeks isn’t a matter of resolving to ‘do something remarkable’ with them. In fact, it entails precisely the opposite: refusing to hold them to an abstract and overdemanding standard of remarkableness, against which they can only ever be found wanting, and taking them instead on their own terms, dropping back down from the godlike fantasies of cosmic significance into the experience of life as it concretely, finitely – and often enough, marvelously – really is.”

Making the most of 4,000 weeks

Burkeman closes with a caveat. His book, he says, isn’t a manifesto calling for abandoning the future for the here and now. The world is, he acknowledges, is pretty fucked up at the moment.

Burkeman is against hope, which is usually seen as a positive thing (you may be seeing a trend), but which he sees as something that incentivizes us to put our faith in institutions, others, the future, the youth — basically anyone but ourselves. Hope causes us to forsake our ability to participate in the solution.

When we give up on hope — on something or something coming to save us — the only thing left to do is to ask how we, in our own small way, can help.

Read more

- Burkeman’s argument that accepting the truth of our limited time will make us better off overlaps with Bill Perkin’s arguments in his recent book, Die With Zero.

- Read more about Egocentric Bias

Love it!